Our previous papers – Kenya’s Real Estate Ecosystem and Anti-Money Laundering Rules & Reporting For The Kenyan Real Estate Sector – provided a detailed look at which actors are involved in real estate transactions in Kenya, and therefore which are able to influence the influx of illicit finance into the real estate market. The reports also highlight the regulations relevant to important actors within the ecosystem and the oversight and reporting mechanisms in place.

In this blog post, we want to dive into how the real estate ecosystem operates for different kinds of transactions, looking at the different actors who could or should be involved in different types of property or land sales and the ways in which the ecosystem should act to prevent money laundering. The purpose here is not to identify explicitly where failings could be happening – rather it is to set out process, to assist interested parties to understand how actors interact with each other.

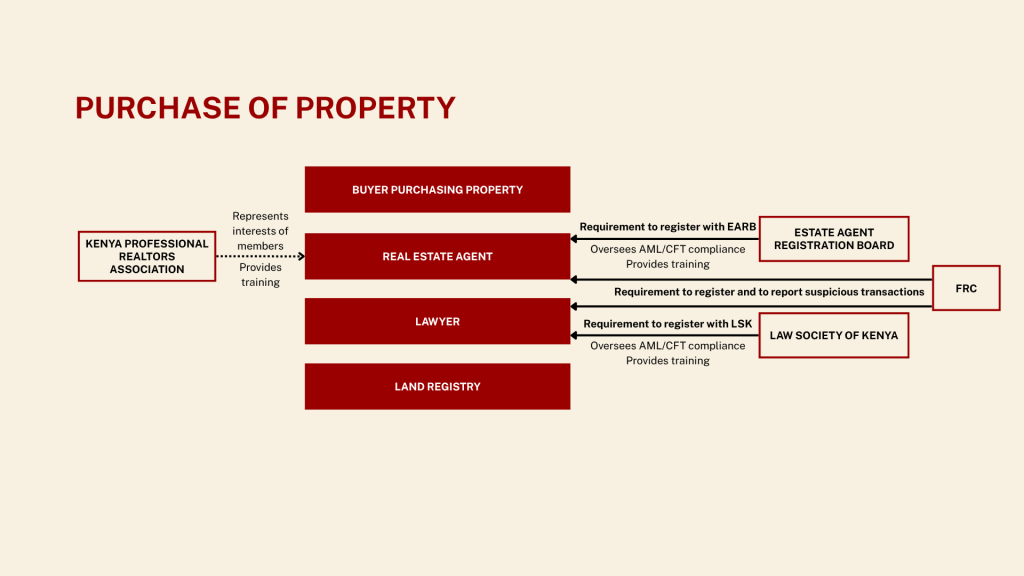

Purchase of a completed apartment or house

A simple property transaction related to the sale of an existing building or apartment could involve up to six actors within the ecosystem, in addition to the buyer and seller. This includes real estate agents, to help purchases and sellers find and sell properties and lawyers, who support the purchase process, including the actual transaction, and may register the purchase for their client. It also includes their respective oversight bodies – the Estate Agents Registration Board (EARB) and the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) – the Financial Reporting Centre (FRC) and Ardhisasa (the Land Registry). It could also include industry associations, such as the Kenya Professional Realtors Association (KPRA).

A transaction such as this has several steps designed to prevent illicit finance entering the real estate market.

Real estate agents are required to conduct customer due diligence on all buyers and sellers they broker deals for, and for all transactions, notwithstanding the value. Part III of the POCAMLA Regulation specifically obliges real estate agents to identify and verify the identity of their clients, determine beneficial owners if the client is a company/legal entity and know the purpose of the transaction. Real estate agents should also record details of the property transaction and payment method. If an agent receives or handles cash of USD 15,000 or above from a client, it should be reported to the FRC. They are also required to monitor for any suspicious transactions that raise questions and, if identified, subsequently file Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs) to the FRC within seven working days. The Estate Agents Registration Board is tasked with monitoring and enforcing compliance of real estate agents with AML obligations, in coordination with the FRC. The EARB can issue guidelines or directives to registered agents on requirements for compliance in implementation of POCAMLA. The Board has disciplinary powers under the Estate Agents Act where it can suspend or revoke an agent’s license for misconduct, including with respect to AML/CFT obligations.

Lawyers are also required to perform customer due diligence and maintain transaction records. If the lawyer knows, suspects, or has reasonable grounds to suspect that a transaction or funds involve the proceeds of crime or terrorist financing, they are legally compelled to file a suspicious transaction report with the FRC without notifying the client. Lawyers are also expected to file Cash Transaction Reports for large cash payments above the USD 15,000 threshold. Additionally, legal practitioners should have internal controls and report to LSK any suspicious transactions. Lawyers are particularly required to pay attention to politically exposed persons involved in property deals, with an emphasis on enhanced due diligence to verify sources of funds and ownership of property. The Law Society of Kenya is the self-regulatory body for the legal profession and should issue guidelines to lawyers, monitor compliance, and liaise with the FRC in relation to AML/CFT. The LSK can inspect law firms for AML compliance and to enforce AML/CFT requirements. Lawyers should suspicious transaction reports to the LSK and FRC.

All of these actors, including KPRA also have soft power influence also over AML/CFT compliance in the sector. This can include on the one hand, providing training or guidance to actors within the system on AML rules but can also include lobbying government for changes to legislation and policy around anti-money laundering and around enforcement of those rules.

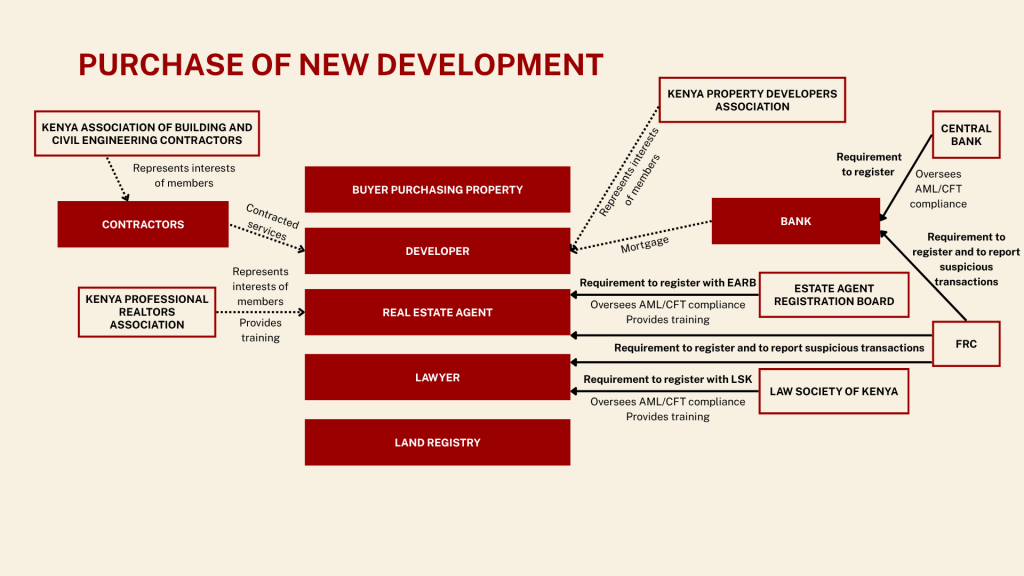

More complex transactions: development projects

When land and property transactions become more complex, the number of actors who are able to influence the introduction of illicit financial into the market also increases. Development projects have been highlighted in our research as one of the riskier types of property transaction for illicit finance and, as can be seen below, these typically involve several further actors within the ecosystem.

How well does this work in practice?

While the sample of cases outlined above shows how the ecosystem works and at what points actors within the ecosystem should step in to prevent and address money laundering, the situation in practice is lacking – particularly when it comes to prevention.

Our report highlights that land and property have been the subject of several cases brought both by the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission and Assets Recovery Agency in recent years, however at the same time actors closely related to the real estate sector are not reporting suspicious transactions to the FRC. In the 2024 Annual Report of the Financial Reporting Centre, it’s recorded that of the 7287 STRs received in 2024, only 1 came from real estate, with zero from lawyers. Similarly in 2023, of the 6131 reports, no reports came from lawyers or real estate firms.[1]

While the subject of challenges in closing these gaps will be the subject of our next paper, notable withing the ecosystem analysis were issues of coverage, resourcing and influence. Many operating real estate agents remain unregistered, oversight bodies do not always have the resources to carry out their role, and political investment into the real estate system means that it can be difficult for institutions to act.

It should be noted here though that we are in a period of change – Kenya is responding to the FATF grey listing by introducing new rules and by enhancing compliance. Notable currently have been efforts by the FRC to get real estate agents registered in its reporting systems.

In 2026 we’ll go more into this topic and look at how these gaps can be closed and the system strengthened as a whole.

Read the full report here

This is the second in a series of reports CiFAR is producing under the Corruption in Paradise research project, Money Laundering through Real Estate in the Touristic Global South. This project investigates how six tourism-focused cities/regions from Brazil, Kenya, and Indonesia address illicit finance in the real estate market.

The Corruption in Paradise research project is coordinated by GRIP (Public Integrity Research Group) at USI (Università della Svizzera italiana) and also includes FGVceapg (Center for Public Administration and Government Studies at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation’s São Paulo School of Business Administration) and the CACG (Center of Anti-Corruption and Governance Studies) at Politeknik STIA LAN Jakarta.

This research is part of the Governance & Integrity Anti-Corruption Evidence (GI ACE) programme which generates actionable evidence that policymakers, practitioners and advocates can use to design and implement more effective anti-corruption initiatives. This GI ACE project is funded by UK International Development.

[1] Financial Reporting Centre, 2024 Annual Report, FRC, p. 14