Overview

Corruption is a major challenge for Nigeria’s development, as international corruption measurement indexes clearly show.1 The current government’s efforts since 2015 in promoting anti-corruption reform – which included a widespread campaign to encourage whistleblowing, the centralisation through the Central Bank of numerous official bank accounts, the participation in the Open Government Partnership and the creation of a Presidential Advisory Committee against Corruption – have been received with mixed reactions by experts and civil society.2 Major risks of embezzlement and money laundering are especially worrying in the extractive sector. Nigeria scores poorly in collecting and publicising data on beneficial ownership,3 while efforts to prosecute corrupt officials, especially in politically sensitive cases are deemed as still insufficient – notwithstanding some recent prosecution cases, including an oil minister and a defence minister. In this regard, civil society has long pushed for the adoption of relevant anti-corruption legislation, especially of a draft Proceeds of Crime Bill (POCA), which would facilitate criminal prosecution for corruption and money laundering.

Asset Recovery

Nigeria is likely one of the most politically active countries worldwide in its efforts to recover its assets looted through corruption. Over the past two decades, cases related to General Sani Abacha and other officials have been used by asset recovery specialists as case studies, referred to as best practice and discussed in political arenas, more than for any other country from the Global South.4

The government of Muhammadu Buhari has particularly put the fight against corruption in Nigeria and the recovery of stolen assets at the forefront of its political agenda. Over the past three years, the Nigerian government has vocally asked foreign governments where Nigerian stolen assets are allegedly hidden to make more efforts to help Nigeria recover these assets. Nigeria was, among other initiatives, one of the key focus countries at the Global Forum on Asset Recovery (GFAR) in December 2017 in Washington DC.

As a result, the government has been able to forfeit, freeze and recover millions of dollars in assets, with officials claiming to have recovered over $9 billion in 2016 alone, the majority of which from domestic sources.5

Nevertheless, the real success of Nigeria’s asset recovery efforts is difficult to measure, due to a general lack of transparency in data around recovered assets. Civil society organisations have repeatedly expressed concerns that relevant agencies and the government release little or no data on recovery processes, including descriptions of the cases, status, amounts and most importantly how the large amounts recovered are to be used. This is especially worrying for domestically recovered assets: while at the international level countries of destination have to some extent negotiated with Nigeria that returned assets should be reinvested in social projects, this has obviously not been possible with assets recovered within Nigeria. The lack of transparency carries a strong risk that, in a country with rampant corruption, recovered assets could end up again in dirty hands, as it has allegedly happened in some of the Abacha returns over the past two decades.6

Moreover, the Nigerian institutional framework for asset recovery is, similarly to the anti-corruption one, arguably unclear and inefficient. Several agencies share the asset recovery portfolio, including the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, law enforcement groups and others, which inevitably carries the risk of lack of clarity and overlapping of roles and rivalry among agencies. A newly established Asset Recovery Management Unit under the Attorney General’s Office has been given the role of overviewing the entire asset recovery portfolio, however this is currently limited by lack of resources and capacity as well as of a common asset recovery policy and of a centralised database of recovered assets.7

The Abacha Loot

In the current political discourse on asset recovery in Nigeria, the case of the $322 million returned by Switzerland between 2017 and 2018 from the so-called Abacha (former President of Nigeria) loot has been at the centre of discussions at both the political and civil society levels. After years of negotiations, the two governments signed a restitution agreement during the Global Forum for Asset Recovery in Washington in December 2017. The assets were then transferred in tranches to the Nigerian Central Bank at the beginning of 2018.

One of the innovative aspects of this agreement is that the Memorandum of Understanding8 has been made public and its negotiations have seen for the first time the involvement of civil society along with the governments. The explicit involvement in the MoU of civil society in monitoring the use of the returned assets was particularly promising. However, a Swiss court made the return conditional to the involvement in the monitoring of the World Bank, which has heavily been criticised9 in Nigeria as an intrusion into sovereign state affairs. As for how the returned assets are to be used, the MoU has also been praised as it stipulates that the assets shall be used for social purposes in Nigeria, namely a “Targeted Cash Transfer” Programme aimed at supporting poor families in 20 Nigerian states by transferring them around 14$ a month.

However, civil society organisations and the media have expressed concerns about the implementation of the agreement and particularly of the cash transfer programme, which was announced to start in July 2018. First, there have been concerns about the real extent of CSO involvement in the decision-making on how the returned $322 million should be used. Civil society, which plays a key role and has extensive experience in understanding the needs of Nigerians in alleviating poverty and reaching sustainable development, has reportedly only been involved when the decision was already made and was afterwards “given” a monitoring role. Hence, there are doubts10 about whether transferring cash to poor families is the best way to fight poverty in a sustainable way and if it would have been better to invest in infrastructural projects with a more long-term impact.

Moreover, the cash transfer programme will feed into the already existing Nigeria National Social Safety Net Program, which has run over the past two years and upon which doubts have been raised as to both its effectiveness and the criteria used to select the beneficiaries.11

There are also questions on the exact selection criteria of beneficiaries,12 with fears13 among Nigerians that the returned assets will be used to target the poor population for electoral campaign purposes, ahead of the presidential election in 2019.

Finally, there are also concerns14 about how the World Bank and CSOs will be able to monitor such a vast programme, across remote regions of Nigeria and involving thousands of citizens.

International Institutional Engagement

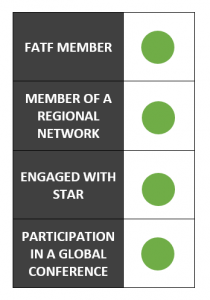

Nigeria is a member of Inter Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA), the regional grouping of the Financial Action Task Force for West Africa.15 It has engaged with the StAR Initiative16 and is a member of the Asset Recovery Inter-Agency Network for West Africa “ARIN-WA”.17

Nigeria was a focus country at the Global Forum for Asset Recovery in 2017. This Forum brought officials together to coordinate next steps in the return of stolen assets. It included a number of recommendations and conclusions, civil society participation was however limited.

Our Reports on Nigeria

Sources

[1] Moreover, 40-50% of people in Nigeria “paid a bribe when they came into contact with a public service in the 12 last months”, according to the 2017 Global Corruption Barometer of Transparency International, https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/people_and_corruption_citizens_voices_from_around_the_world

[2] See for example https://guardian.ng/opinion/buharis-anti-corruption-fight-and-the-rule-of-law-2/

[4] See for instance Ignasio Jimu, Basel Institute of Governance „Managing Proceeds of Asset Recovery: The Case of Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines and Kazakhstan”, 2009.

[5] https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/nigeria-recovers-9-billion-dollars-stolen-money_us_5752daefe4b0c3752dcdc7bf (visited 10th August 2018)

[7] Conversations with various organisations and institutions during CiFAR’s mission to Nigeria, 25-29 June 2018. See also “Nigeria: Experience on Asset Recovery. Nigeria CSO Country Report for Global Forum for Asset Recovery”, Aneej and SERAP, December 2017.

[8] The MoU is available under https://www.newsd.admin.ch/newsd/message/attachments/50734.pdf

[13] https://allafrica.com/stories/201807190361.html

[14] https://www.vanguardngr.com/2018/07/abacha-loot-redistributing-the-illicitly-acquired-funds/

[16] https://star.worldbank.org/content/milestone-stolen-asset-recovery

[17] https://www.unodc.org/westandcentralafrica/en/launch-the-asset-recovery-network-arinwa.html