With the help of their corrupt networks, kleptocrats steal billions from their citizens every year. One of the tools the European Union has at its disposal to fight kleptocrats are sanctions that freeze their assets.

On 6th of March, at a Brussels event co-organised by our partners at Transparency International EU, CiFAR launched EU Sanctions Watch – a new online tool that documents the people subject to these sanctions and provides information about the EU sanctions system. We also launched a new research study analysing the effectiveness of this system as a tool against cross-border corruption. You can download the report here.

EU Sanctions Watch tool

EU Sanctions Watch is a one-of-a-kind resource on misappropriation sanctions. It collates and transforms raw data into a visualised list of the people subject to sanctions, including with their portrait, information on aliases, sanction expiry dates, publicly reported estimates of assets hidden in EU member states and reported assets frozen or confiscated.

Besides the detailed individual profiles, the platform provides the newest research on the topic of misappropriation sanctions, overview of the main terminology, as well as links to legal documents. Contacts of national competent authorities, and guidelines for the private sector are also included.

This tool is designed to help journalists in their investigations, and assist the financial, legal and real estate professionals and luxury goods retailers in identifying clients they should not have dealings with. For civil society, this tool will help to better draw attention to sanctions that are in force, advocate for keeping the sanctions in place and bring attention to the need to return the assets to countries of origin.

Sanctions against the misappropriation of state assets

The misappropriation sanctions refer to the EU sanctions imposed on foreign kleptocrats to address the suspected theft of public funds – in EU terminology the “misappropriation of state assets”. They take the form of asset freezes, which make funds and economic resources of the designated person unavailable for the period they are in force.

The EU applied these sanctions after the kleptocratic regimes were toppled in Tunisia and Egypt in 2011 and Ukraine in 2014. In all of these three cases, the uprisings removed from power leaders and their close associates who had long been suspected of stealing vast amounts of public wealth from their countries and hiding this wealth overseas. The misappropriation sanctions were applied only in these three cases, and as our report shows, despite successfully signalling support to the new governments, their success in recovering stolen assets has been very limited. This is mainly due to legal challenges to the sanctions in front of European courts by designated individuals, as well as insufficient link between these sanctions and an asset recovery mechanism.

Who are the sanctioned individuals?

In Tunisia, the “Jasmine Revolution” that broke out in December 2011 eventually led to the end of a 23-year-long reign of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and started what became known as the Arab Spring.

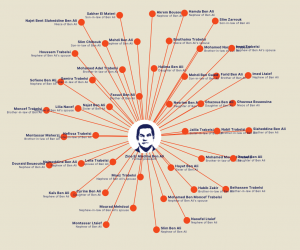

It is believed that Ben Ali’s family has hidden as much as US$17 billion in bank accounts across the world. This is why the European Union has imposed the misappropriation sanctions on Ben Ali and other 48 individuals, mostly part of his extended family network.

After Marwan Mabrouk, a businessman and former son-in-law of Ben Ali was delisted in January this year, 46 individuals remain on this sanction list.

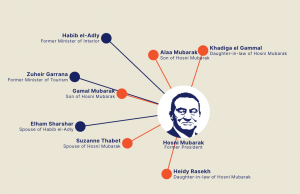

In Egypt, former president Hosni Mubarak, his family and close circle of advisers that were in power for a period of 30 years are alleged to have enriched themselves through partnerships in numerous Egyptian companies. Mubarak’s family fortune has been estimated to be between US$40 to $70 billion.

The EU initially sanctioned 19 Egyptians suspected of corruption but today only 9 remain on the list. The next review and a renewal of the list is due on 21st March 2019.

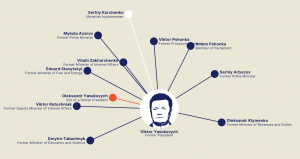

In Ukraine, the use of brutal force against protesters of the Maidan revolution by president Viktor Yanukovychand his government, together with the misuse of power and pressure on independent press and political opponents, all contributed towards the ousting of the president and his allies.

“The Family” – Yanukovych and his associates – allegedly embezzled as much as to US$37 billion by moving state to offshore accounts and companies they controlled. Many Ukrainian designees challenged the sanctions and today only 12 from the initial 22 remain on the list, with Andrii Kliuiev being removed most recently in March 2019.

Fighting kleptocracy and cross-border corruption

What becomes clear when looking at the networks of sanctioned individuals in all three countries is not only the vast amounts of money embezzled that all three regimes have in common but also the spider web-like character of their network that allowed them to misappropriate the public funds of their countries.

Uncovering connections between individuals, their assets and their companies is a first step to make the sanctions list more transparent and more informative and fight against cross-border corruption and kleptocracy more effectively. Our new online tool EU Sanctions Watch aims to do just that.