The announcement of the Jersey return of GBP 3 million – the latest cross border return to Kenya – was welcomed with pomp and gladness by Kenyans in general, because these had been a long coming return! The signing and announcement of the Agreement for the recovery, transfer, repatriation, disposition and management of recovered asset was completed on the 28th of March 2022. However, to date, public information on the return has been limited.

Background and the agreement

A total of GBP 3.82 million was confiscated from Windward, a company that plead guilty to having possession and acquiring of proceeds of criminal conduct in 2016. Former Kenya Power and Lighting General Manager Samuel Gichuru and former Minister of Energy, and later the Minister of Finance Chrysanthus Okemo had already by then been convicted in the UK and sentenced to serve 14 years in prison in relation to this, but both had contested the extradition charges in Kenya. The extradition case for Okemo was lost in Kenya on 30th November 2022; while Gichuru’s case has been suspended due to his illness, and is yet to be determined.

The asset sharing agreement between the Bailiwick of Jersey, who recovered the assets, and the Government of Kenya, of the GBP 3.82 million, stipulated that GBP 3 million will be repatriated back to Kenya while the GBP 820,000 covers the costs that the Jersey government had incurred in prosecuting the case.

Participation and transparency

Principles of transparency and accountability have been pivotal in the agreement, as well as the overarching Framework for the Return of Assets from Corruption and Crime in Kenya (FRACCK). In the more than one year since the public signing and announcement that the asset return will be done through third parties – Crown Agents and Amref who were to handle 90% and 10% of the return respectively – implementation has however been delayed and information difficult to access.

In particular, due to the delayed start, there have not yet been any follow-up updates on the project published and while it was reported that Crown Agents would facilitate in the procurement of medical equipment and Amref would build capacity of the medical personnel, it is not public how these priorities were arrived at, how the third parties were selected and what progress is being made.

Inquiries through various channels have highlighted the fact that a problem lay in the fact that the negotiations were long and protracted. From the Kenyan side, a government official has highlighted that the Kenyan government was always negotiating from a weaker position because it was perceived that the internal weaknesses that led to the corruption have not been fully addressed. On the Jersey side, they observed the challenge of there being many divergent interests and changes of officials on the Kenya side every so often.

Missing inclusion from the budget

Further inquiries have revealed that the signed agreement in March 2022, and subsequent signing of the subsidiary agreement by Ministry of Health as the implementing party, should have been followed by the inclusion of the expected income into the National Budget approved in July 2022. However, it was not.

This omission in ensuring the Appropriation in Aid budget line for the return within the health budget was eventually corrected in the March 2023 Supplementary budget for Fiscal Year 2022/23 which ends in July 2023. As a consequence, the transfer to the implementing partners could only be effected after this inclusion of the funds into the FY2022/23 National Budget. It is therefore safe to say that we are only now five months into implementation even though it is 17 months since the announcement.

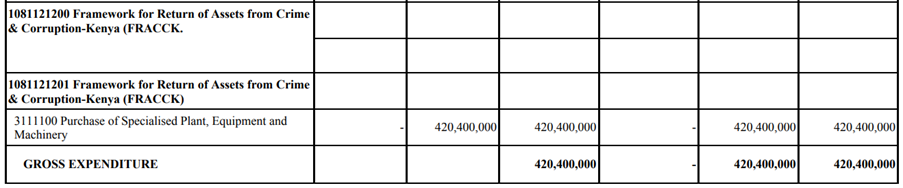

The table below provides the excerpts from the FY2022/23 March 2023 Supplementary budget.

As the agreement stated that reporting will be done halfway into implementation, the mid-point report should therefore only be expected any time soon.

Lessons learnt so far

Given that this was the first return under the FRACCK agreement, a few lessons learnt can already be taken forward for future returns:

- Firstly, while the Jersey return was lauded for its involvement of non-state actors as the service level providers, the selection process was not open or competitive. An open process would have led to more civil society engagement in and greater public understanding of the return.

- Secondly, the mechanism for monitoring implementation and the impact of the interventions also seems limited to the state actors. In other words, there does not seem to exist an inbuilt mechanism and platform for engaging the public and civil society in discussing progress in implementation. Given that there were delays due to funds being missing from the budget, greater civil society involvement could have addressed this sooner.

- Thirdly, the negotiations over the disbursement of the funds also only engaged the State parties. The involvement of non-state actors would have assisted with input on priorities and, at the same time, would have enhanced access to information and accountability as more actors would be informed on the progress being made regularly.

This blog was written by Rose Wanjiru, CiFAR.